The Early History of Plainfield, Vermont from the Beginning to 1880

|

The contents of this page are provided by the Plainfield Historical Society, a 501(c)3 non-profit organization.

Written by Susan Ross Grimaldi, M.Ed. (Based on research and archival contributions to the Plainfield Historical Society by Cora Copping, Myra Himelhoch, Flora Bemis Cate, Baxter Bancroft, and others) Special Thanks to David Ferland, Dan Gadd, Dale Bartlett, Richard Petit and members of the Plainfield Historical Society, past and present. Contents The village of Plainfield is nestled along the waterways of the Winooski River and the Great Brook. These waterways held plenty of trout pools that provided excellent habitat for large Brook Trout. Plainfield is flanked by hills having spectacular views of Camel's Hump.

Within the Town of Plainfield sits Spruce Mountain at 3037' elevation, hosting a fire tower that provides a panoramic view. In the early days there was a logging camp on Spruce Mountain. In the early days, Plainfield had no electricity and people traveled by cart and oxen. They used snow rollers instead of plows to pack the snow allowing sleighs to slide over it. In those early days we could have seen a buggy drawn along by a trotting horse, bells jingling as it stirred the dust heading to the hitching post near the livery stable on Main Street. At one time there were 11 separate school districts in the Town of Plainfield, each having a teacher and 10 to 14 students. Plainfield used to have a train station with daily wood fired steam engine trains that traveled between Montpelier and Wells River carrying passengers, lumber, and granite. The route was so curvy that in those 38 miles there was only one full mile that was straight and this was in Plainfield. It took 6 cords of wood to make enough steam for the round trip. Near the train station stood a sawmill that cut local ash wood for a tennis racket factory in Pawtucket, R.I. There was a granite shed that made statuary carvings, as well as a creamery where the farmers brought their milk for collection to be loaded onto the train that carried it to Boston. Three miles south of town there was a natural sulphurated spring that once led to a popular destination spa known as the Plainfield Spring House. It housed baths as well as a bowling alley and dance floor and is said to have rivaled Saratoga Springs as a health spa. The Plainfield Spring House burned down in the fall of 1884. There was a tavern and one of the earliest Vermont general stores. There were several ministries and churches, and a couple of doctors. There was a slaughterhouse, a coffin maker and a funeral parlor. Weary travelers took lodging at the Pleasant View House, which was later rebuilt and renamed it the Bancroft Inn. It had a large suspended dance floor and still does today. Outside the Inn there was a large porte couchere that reached across route 2 providing shelter for travelers as they stepped out of their carriages during a snow or rainstorm. The horses for the lodgers were cared for in the livery on the corner across the street. About 450 million years ago, the first of two major mountain-building events occurred. Tectonic plates collided closing an ancient ocean and forming the Green Mountains. The ocean sediments on the continental edge were compressed and piled up by the force of the collision and formed the bedrock in Vermont. The deeper rocks responded to the high temperature of the Earth's mantle and to the increased pressure by folding. These rocks underwent great compression transitioning to form crystalline structures. Some of the sediment melted and bubbled back up to the surface. Most of the rocks in Plainfield are azoic, meaning having no trace of life or organic remains. To look for fossils, one would need to travel to the Champlain Valley. On the other hand, the granite that abounds in Plainfield is not found on the west side of the Green Mountains.

Following the tectonic plate collisions, a long period of relative quiet followed, during which the newly formed mountains were eventually ground down by erosion. If the sediments that eroded off the Green Mountains were piled back up they would create mountains at least eight thousand feet high if not higher. During the period after the Green Mountains formed they were reduced to half this height by weathering. At this time the Winooski River was young and Vermont had a tropical climate. It was warm and swampy, with tropical fruit growing in the river valley. Then, beginning around three million years ago a change in ocean currents led to cooling of the poles, which marked the beginning of the Glacial Period. During the last advance of ice out of Canada, the Laurentide Ice Sheet buried all of Vermont under 1 to 2 miles of solid ice lasting to as recently as 13,000 to 10,000 years ago. Glaciers covered New England and beyond. The glaciers scoured many meters of sediment from the mountainsides and laid down a massive layer of glacial till that became the parent material for many of the soil types in Vermont. Cape Cod and Long Island are made of material plowed up by the ice sheet and deposited in the ocean as a glacial moraine. Ten thousand years ago, as the glaciers retreated from Vermont, they left behind a barren landscape. Tiny tundra plants soon colonized the rubble, followed by hardy willows and alders. Woolly mammoths, mastodons, saber-toothed tigers, caribou, and wolves eventually roamed this rugged landscape. The melting glaciers created new lakes and it is thought by Geologists that for a time the Winooski River may have flowed backwards to the Connecticut River, and that a lake 20 miles long covered the area where Plainfield and the neighboring towns now lie. Archaeologists have discovered evidence of scattered human settlements from 12,000 years ago. Archaeologists call these original Vermonters, Paleo-Indians. The Winooski Valley warmed and dried, making a natural trail crossing this region.

Native people made use of the river as it provided a remarkable way to cross the state. They called the river, "Winooski-Took," meaning Onion Land River, named for the wild onions that grew along its banks. Abenaki, Mi'kmaq, Penobscot, Maliseet, and Passamaquoddy peoples used the Winooski River and surrounding trails as a major travel route between the Connecticut River and Lake Champlain. These early inhabitants followed the Wells River going westward, to what is now Groton State Park. Then, by making short canoe portages, they were able to paddle on Ricker Lake, Groton Lake, Kettle Pond and Turtlehead Pond, finally joining the Winooski River in Marshfield. Continuing on they passed through what is now Plainfield Village heading west on the Winooski River, going with the flow. From there they traveled northward, following the Winooski River and arriving at Lake Champlain. They also traveled in the opposite direction from Lake Champlain to the Connecticut River and far beyond. These pristine waters provided abundant fish and the woodlands were good hunting grounds. There is evidence showing that original native people were living in what was to become the Plainfield area as late as the 1780s or 1790s. There was an Indian village in East Montpelier, on the Winooski River bank located opposite the mouth of the Kingsbury Branch. It contained as many as twelve large fire pits each six feet in diameter. Small rocks had been pounded into the ground, distinctly marking the pits. About half a mile up the Kingsbury Branch was a cornfield of an acre. Near this site an iron axe was found. * *Drawn from research of Mr. Charles H. Heath, who devoted considerable time to the study of Indian occupancy of this region. Ownership of these lands was greatly disputed between the French and British. The various English colonies also were vying for it. Massachusetts got a toehold first, and then New Hampshire began claiming ownership when their governor divided it into townships called grants to sell the land. Then the King of England proclaimed that this area was owned by New York and the New Yorkers tried to drive off the settlers that had already paid New Hampshire for their land. The Green Mountain Boys chased the New Yorkers out of the Grants, as the land that would later become Vermont was then called.

When the Revolutionary War began, the quarrel was forgotten while the colonists drove the British out of New England. After the war, a tug-of-war ensued between Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and New York over the "Grants" as each attempted to get Congress to grant ownership. While this was happening, the Grant people (the original settlers who had purchased land from New Hampshire) declared themselves to be the Independent Republic of Vermont. When Vermont set up its own government in 1777, they kept all of the towns that had been granted by New Hampshire as they were. Land that hadn't been granted by New Hampshire was declared to be vacant land belonging to the State of Vermont. Plainfield was in a "vacant area". James Whitelaw was the chief surveyor for the northern portion of Vermont. His job was to get all of the "vacant area" land divided up into standard sized townships, each being six miles square. In the course of his work he discovered that there was a piece of land lying between Marshfield and Montpelier that hadn't yet been granted. This piece was less than half the size of the usual township. It was one of the many, "gores", or bits and pieces of land left over after the regular townships had been laid out. Whitelaw marked one corner of this gore and called it, "St. Andrew's Corner". This section would later become known as Plainfield. The state owed Whitelaw and his assistants quite a large sum for their work as surveyors. Being unable to pay them in money, the state offered them payment in new lands, one of which was St. Andrew's gore. Whitelaw and his assistants were expected to "cultivate and settle" their new property, but they wanted to sell it. Ira Allen, a Green Mountain Boy, during the Revolutionary War, purchased most of St. Andrew's Gore. Ira had a special plan for it. He wanted to start a college in Burlington, and to help it along he offered to make a gift of a yearly sum of money, which he would collect as rent from the new settlers. He expected that he could get the new settlers to pay rent in the form of wheat, pork and butter, which he would turn over to the college. Part of Ira's plan succeeded. The college, which later became known as the University of Vermont, was founded in Burlington. But part of the plan failed. Ira had appointed Jacob Davis of Montpelier to rent the land while he was in Europe. Davis had misunderstood and instead sold the land to the settlers. By the time Ira had returned almost six years later, most of his land was gone. Davis had sold most of the land. This caused a great deal of trouble. Ira's nephew, who was a lawyer, tried to fix things for his uncle. He paid the University the money that Ira had promised. He then tried to collect money from the settlers who had already bought their land from Davis. Lawsuits dragged on for years. In the end the settlers got the worst of it and had to pay again for their land. Davis divided the rest of the gore into regular sized lots of about a half a square mile each, or 320 acres. The pioneers began to settle in Plainfield in the 1790's. Two of those first settlers were Seth Freeman and Isaac Washburn. They had heard fabulous stories about the fertile land in Vermont, and in the fall of 1791 they set out on foot from New Hampshire to investigate. They had heard from Jacob Davis, Ira's agent, that there were lands for sale in St, Andrew's. This new wilderness had not yet been divided into lots and no one was living there. The two young men liked the land and each selected a piece to buy and settle on. This was called making a "pitch". The settlers' first task was to make a clearing in the woods. Trees were cut down, and the stumps were burned to prepare the ground for crops. They felled trees and used the logs for building houses, fences and bridges. They made furniture, kitchen utensils and farm tools, and put up a supply of firewood necessary for cooking and heating. They stayed through the fall, living in simple shanties that they had built, returning to New Hampshire when cold weather set in. They returned to St. Andrew's with their families in winter by sleighs loaded with their belongings. Winter was the best time for traveling with families as the sleighs glided easily over the snow. They relied on hunting moose, deer, partridge and rabbits, and when spring arrived they planted gardens for their survival.

In 1793 there were three more pitches made by Joseph Batchelder, Theodore Perkins, and Joshua Lawrence. These first settlers were to abide by the charter granted to the town, which stated that each grantee was to plant five acres of land, erect one house at least eighty feet square on the ground floor, and have one family on each share of land. These first houses were log cabins. By 1797 there were thirty families in this new settlement, and by 1800 double that number. During the early years, the pioneers had relatively few domesticated animals. On the newly cleared land they planted corn averaging better than 40 bushels per acre. During this time the farmers ground their own corn. A bowl-like shape was cut in a tree stump, and a sapling was bent over it having a heavy stone attached. The dry corn kernels were placed into the bowl and the counter weighted stone was lifted and dropped to pound the corn. They grew all of their own wheat, averaging over 20 bushels an acre. It wasn't long before a dam was built on the Winooski and the water harnessed to turn the water wheel and millstones to grind grains for the town's people. Charles McCloud erected the first sawmill in Plainfield, with a wooden dam on the Winooski River in 1798. At that time in history, what would soon become the village site was a mud slab known by the names, Mill Privilege and Mud Hollow. It was also called "Slab Holler" because of the fact that the first buildings were made of wood slabs. Grass was the great natural crop that fed the sheep dotting the hill pastures. Horses were needed to work the farms, and for travel. Cows became numerous, along with chickens, eggs and crops of potatoes. Plainfield farmers produced milk, butter and cheese. Most village homes had apple trees. Every farm had an apple orchard. There were plenty of old Maple trees. In the early years boys and girls of Plainfield grew up drinking sap from the tap buckets. Mothers would show them how to boil it down to little cakes or gummy syrup that they could pour over snow for a sweet treat. When gathering the sap, pails were yoked over the shoulders or dumped into a tub-topped sled, which was hauled by oxen to the sugarhouse. By 1800 there were church services and town meetings. A blacksmith shop sprang up, as well as a tavern. These pioneer families began thinking about community projects such as building roads and laying out a Common. They thought that they should elect officers just like other towns. But when they looked up the town charter, they discovered that St. Andrew's had never been legally named or incorporated as a town. One of the inhabitants at that time suggested that the name be changed to Plainfield after his hometown in New Hampshire. He made his suggestion attractive by offering to provide the town with its first set of leather-bound record books. The townspeople drew up a petition asking the legislature to incorporate the town as Plainfield. The petition was granted in November 1797, but for reasons unclear the village was not incorporated until 1867. John Chapman kept his promise and bought two leather-bound books and gave them to the town to record all of the earliest land sales and town meetings. As late as 1804, some folks didn't have chimneys on their houses. Stones were laid up only a few feet inside the house forming a very short chimney and the smoke was allowed to go out, if it would, through a hole in the roof. The roofs were made of large pieces of elm bark tied on with handmade cord made from the elm bark. Sometimes a storm would blow these bark slabs off in the night and they would have to tie them back. This chimneyless smoke-hole arrangement would often catch fire and houses did burn down occasionally. There was a special additional use for the hardwood trees. They could be felled and burned, and the ashes made into potash, called salts of lye. The ashes were collected and water was poured through them, a process known as leaching. The liquid was boiled in large iron kettles until a thick crust formed on the bottom. This crust was the potash. These salts were used to make fertilizer, glass, soap, gunpowder and for dyeing fabrics. Around that time most country stores began to operate potash works so farmers could bring their ashes to the store and have the leaching and boiling done for them. Philip Sparrow started the earliest potash works in Plainfield in 1804. He also opened the second general store and a lumberyard in Plainfield. Mount Tambora, in Indonesia, erupted in 1815, making the summer of 1816 very cold, causing widespread crop and business failures, including that of Mr. Sparrow's who decided to pack up and try his luck out west. Amasa Bancroft built a blacksmith shop on what was then called "the island", which adjoined a millpond near the junction of the Winooski River and the Great Brook. A blacksmith shop in those days was a center of trade and gossip. Farmers would drop in to see the latest new tools, or get an old cooking pot or wagon part repaired. They would bring in oxen to be shod. It was an exciting spectacle to see Amasa hoist the balky beast up on an ox-frame and make its feet fast in preparation for nailing on the new metal shoes. During the days of horse and buggies, an old fellow once told me that to go from Plainfield to Cabot and back would be an overnight trip. He would go 12 miles one day, spend the night in Cabot, and if he were traveling in winter, there would be a hot rock placed in the bed to keep his feet warm. Then, the next day after he did his business he would hurry back to Plainfield. In about 1801, Amasa Bancroft, his wife and infant son Tyler, rode horseback to visit a farm family off East Hill Road. The farmer gave them a slab of fresh meat. On their way home the wolves began to assemble to the rear of the travelers. The wolves were coming nearer and nearer—so near in fact that the Bancrofts threw the wolves the fresh meat. The family got home safely, but very soon the wolves came howling around their house. The Catamount (Mountain Lion) was known as the most fierce and ravenous animal in the state. It was never abundant but occasionally they would attack a man on horseback and kill the horse but not the man. In addition there were abundant black bear, rabbits, hares, fox, hedgehogs, skunks, raccoons, woodchuck, otter, mink, sable, ermine, muskrat and ruffed grouse (known as partridge). There were also bobcat, lynx and beavers. The charm and beauty of Plainfield is ever present due to the numerous historical buildings that remain, surrounded by the same hills, along with the waterways that are all much the same as they were originally. When walking through the village today with a little imagination we can see the old hitching post on Main Street. We can hear the clomping of horses as a buggy is drawn along the dirt road in front of the Methodist church. We can gaze at the dam below the bridge that crosses the Winooski River and know that this was used to power a sawmill and a gristmill. When we step inside what was originally one of the oldest Vermont general stores, and walk across the original floorboards, and can imagine folks gathered round the cast iron parlor stove, talking and warming up before heading back to their hill farms by sleighs pulled by oxen. These original buildings give the Plainfield community continuity between generations of people who have lived here before us.

We have preserved our history and can enjoy this special charm as we continue into the future. Plainfield has been shaped by tradition. Our history has, in part, created our culture, and this legacy has become our gift to share with our guests and visitors. |

Vertical Divider

This is one of the oldest structures still standing in the village today. It was the original Methodist meeting house, built in 1819. In 1852, when the Baptist Society purchased it, the building was moved to its current location on Main Street (in front what is now the Plainfield Coop). The Baptists used it for 20 years and in 1871 the building was converted to a store called St. Cyr's, which is pictured here. It now houses Plainfield's Municipal Offices.

This is a photo of the Wheatley Tavern, which was built in the village center around 1825. It is located on Main Street across from what is now Positive Pie Restaurant. This brick building had a two story Victorian porch and a Federal style façade. This photo was taken in 1910.

Soon after building the Wheatley Tavern around 1826, Mr. Wheatley built two brick buildings exactly alike and next to each other, across the street from the tavern on Main Street.

The two identical Wheatley stores changed ownership on a regular basis. They were known as, Batchelder and Foss, H.H. Dewey and Ross, Bartlett, Maxfield and the Cutler Stores. Here you see it when it was named Perrin and Cutler. This photo was taken around, 1890. After Clem Kellogg purchased the store it remained Kellogg's until 1978, when it became PLR Manwell's.

When gathering the sap, pails were yoked over the shoulders or dumped into a tub-topped sled, which was hauled by oxen to the sugarhouse. This man was boiling the sap right in the sugar bush.

This is the Batchelder House located on Mill Street at the foot of Barre Hill Road. It was built in 1840, by Nathaniel Sherman in the Federal style, with brick that had been manufactured in a nearby brickyard.

Arthur Batchelder began a hardware business at this residence in 1903. It is located in the small shed shown in the center of the photo. He sold lightning rods, indoor plumbing, water pumps. Unassembled machinery would come in on the train and was unloaded and reassembled on this site and sold to farmers. Mowing machines: hay loaders, rakes and spreaders were in demand as farming became more mechanized. In the cellar of the brick structure he had a fish and grocery store.

A medicinal spring was discovered on the Great Brook. The Spring House was built in 1850, by Moulton Batchelder in the southern part of town along the banks of the Great Brook, three miles out from the village, in an area known at that time as Perkinsville. As a health spa, it is said to have ranked with Saratoga Springs. The presence of Sulphureted Hydrogen gas was known to cure diseases, particularly those of the skin. The two–story wooden frame structure had a dining room, upstairs ballroom and accommodations for twenty or more boarding guests. The arrival of the railroad made the Spring House easier to reach and brought additional visitors.

The Batchelder Mill was constructed in 1877, the same year that the Cass Mill had burned down. It was placed on the 40 by 100 foot foundation of the Cass Mill. It was located along the eastern bank of the Winooski River, in what is now the Municipal Park, on Mill Street.

The grinding capacity of the gristmill was between six and eight hundred bushels per day. They ground oatmeal, corn meal, rye meal, bone meal, graham flour and wheat flour. I was told that children were allowed to slide down the wooden grain chutes for fun.

Built in 1830, the Plainfield Hotel had a thriving business during the horse and buggy era.

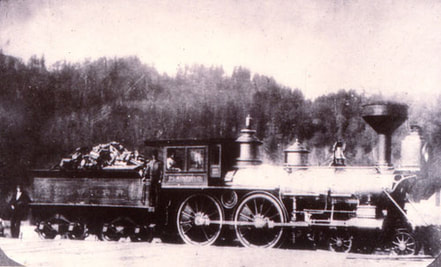

The arrival of the railroad brought new industries, employment opportunities, and an increased need for housing. The train stopped at the Plainfield Station located near the cemetery in what is now the Park and Ride parking lot.

Businesses in the village benefited by the railroad's arrival and provided a period of economic prosperity.

There was a granite shed located near the railroad station that made carvings.

This is a photo of the old steam engine train, called the "Plainfield". It was built in 1873. It had 14" by 22" cylinders and a 60" diameter driving wheel.

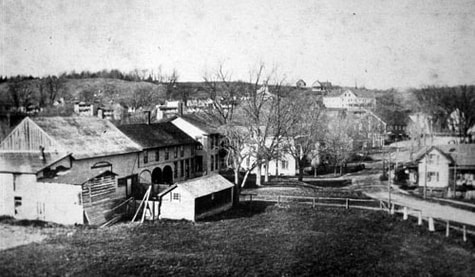

This is one of the earliest photos that we have of Plainfield Village. It was taken around, 1880. The population had grown slowly, reaching 80 families by then.

|